Someone spoke to me about a common out-parameter C++ abstraction that gets used across many code bases and the potential performance left on the table, sparking a curious investigation! Let’s start with the results:

Free Performance is left on the table?!

The typical implementation of out_ptr/ptr_to_ptr/out_ptr that cannot friend the pointer variable inside of std::unique_ptr leaves performance on the table, leading me to believe it is time to modify some of the standard library implementations to check just how much faster a non-UB, friended implementation of out_ptr might be.

Of course, it can’t just be about the destination: so it is time for a journey! (If you’re not interested in the journey, scroll down to see some graphs.)

Starting down the Path

The code in question is the out_ptr technique used on std::unique_ptrs and friends:

#include <some_lib/out_ptr.hpp>

#include <memory>

extern "C" c_api_err_num clib_init_thing(void** handle_out);

extern "C" void clib_destroy_thing(void* handle);

struct destroy_thing_deleter {

void operator()(void* handle) const {

clib_destroy_thing(handle);

}

};

int main(int, char*[]) {

std::unique_ptr<c_handle, destroy_thing_deleter> my_handle(nullptr);

// out_ptr(p) performs ~*~magic~*~

c_api_err_num err = clib_init_thing(out_ptr(my_handle));

if (err == C_API_DOOM_GLOOM) {

/* oh nooooo */

}

// my_handle.get(), from here on, has the real deal!

}

The explanation is that it takes advantage of the C++ Standard’s well-defined lifetimes for temporaries that are created for an expression such as a function call. If you return some C++ structure Thing from the function out_ptr( my_handle ), the events go like this:

- A

Thingcan be constructed (and returned) by the call toout_ptr( my_handle ). - Said

Thingis kept alive for the duration of the expression it is used in. - It is destructed when that expression returns, and before the next statement / expression executes.

Using this knowledge, we can construct a Thing that holds a void*, pass a pointer to that value (a void**), and then when the object destructs we can stuff that value back into whatever needs it (in this case, back into my_handle, since the destructor will be called after clib_init_thing has finished!

Using these guaranteed sequence of events to create this out_ptr( my_handle ) abstraction is incredibly common. Tons of companies have their own home-rolled ones, mainly to work with std::unique_ptr. At this point, if so many people have rolled their own, then it becomes common to ask: well, why isn’t this in the standard?! I asked the question of the company I was visiting, and they had the same question… so, it seems like there is some common ground for getting this into the standard! Among the chief concerns, however, was that when measured the typical implementation done outside the standard library has a higher cost than necessary.

Oh, dear.

Claims like these must be substantiated. Tens, perhaps hundreds, of companies – from startups to Fortune 100s – have this kind of abstraction in their code base, and it would not be great for C++ if such a simple abstraction had a noticeable or measurable difference in performance.

Gathering Evidence

I created a library called out_ptr, and set out to perform the measurements. Other people presented to me company-internal findings and assurances for their case: could I reproduce their findings on my own hardware and have a non-anecdotal, factual backing to my desire for out_ptr in the standard library? Thusly, like any good science-oriented person, we repeat the study to see if it is reproducible.

The out_ptr library’s implementation contains one key difference. To determine if we can create a faster out_ptr without actually going to the effort of modifying the standard library, we perform an aliasing technique. This lets us obtain a reference the data directly in a std::unique_ptr. Thusly, there are 2 implementations: clever_out_ptr and simple_ptrtr. The simple version uses .release(), and then performs a .reset() with the output value stored in the temporary. The clever version writes directly into unique_ptrs memory.

The Benchmarks

The benchmarks were written using Google’s Benchmark. Benchmark takes care of measuring environmental overhead and iterating enough times to produce a statistically valid measurement. We then perform a number of repetitions of these iterated benchmarks to collect data to perform some basic analysis. There are 2 kinds being tested: having a pointer that was already created and simply resetting into it (“reset”), and having a fresh pointer that was created for each loop (“local”). C versions were also written as a baseline, but our primary concern is the manual vs. the simple_out_ptr versus the clever_out_ptr versions. Here’s what the C code version and out_ptr-abstraction versions for a local pointer looks like:

#include <benchmark/benchmark.h>

// fictional C API

#include <ficapi/ficapi.hpp>

void c_code_local(benchmark::State& state) {

int64_t x = 0;

for (auto _ : state) {

int* p = NULL;

ficapi_handle_create(&p);

x += *p;

ficapi_handle_delete(p);

}

int64_t expected = int64_t(state.iterations()) * ficapi_get_data();

if (x != expected) {

std::abort();

}

}

BENCHMARK(c_code_local);

// ...

void clever_out_ptr_local(benchmark::State& state) {

int64_t x = 0;

for (auto _ : state) {

std::unique_ptr<int, ficapi::handle_deleter> p(nullptr);

ficapi_handle_create(phd::clever_out_ptr(p));

x += *p;

}

int64_t expected = int64_t(state.iterations()) * ficapi_get_data();

if (x != expected) {

std::abort();

}

}

BENCHMARK(clever_out_ptr_local);

The full code is here, and there are instructions for building and running all of the tests/benchmarks with CMake.

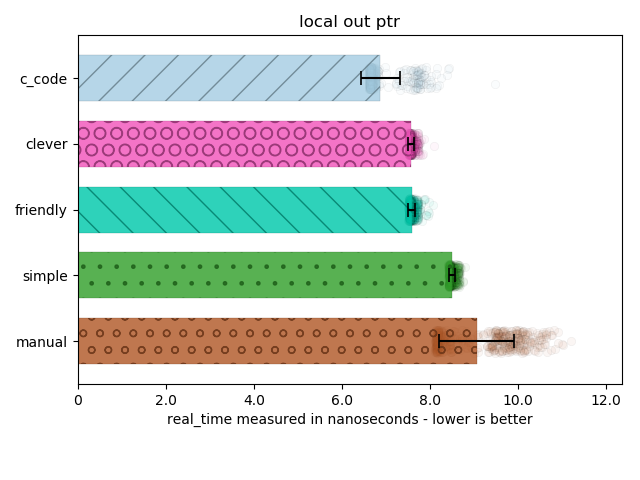

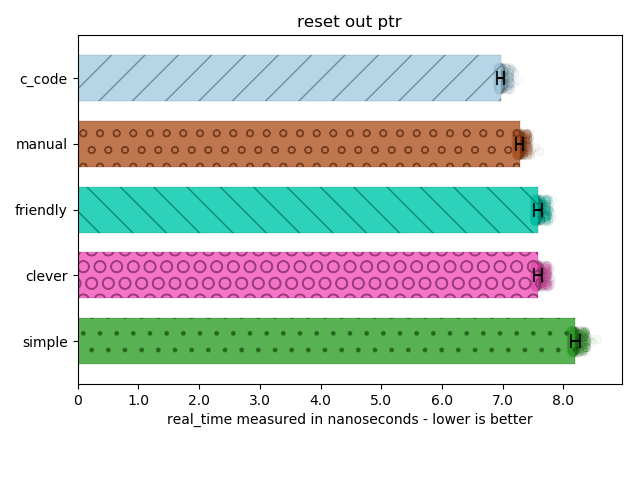

The graphs below come from a dedicated Core i7 machine, compiled with the usual flags for each platform (-O3 on g++/clang++, /Ox for VC++), we generate the values of the runs in JSON format and then send them to a quick python script I wrote that can output their values for me to inspect in pretty graph form. The graphs have error bars representing the standard deviation, bars up to the mean, and transparent scatter plots indicating the distribution of 1000 multi-iteration benchmark samples. We sort from fastest to slowest, and the color remains the same for each technique (c_code versus simple_out_ptr versus clever_out_ptr used):

You can clearly see here that the clever_out_ptr has a statistically significant performance advantage: it is outside two or even three standard deviations. The raw data that is available publicly in the GitHub repository also reports an Index of Dispersion that is far less than 1% (e.g., the Index of Dispersion is on the order of pico- and femtoseconds while the measurements are on the order of nanoseconds). This means the results are not subject to wild variance and hold significance.

Perhaps my only concern is what is happening with the c_code version. It is unclear to me what is going on, and I will need to ask others and disassemble the code to understand it. (If you look at the code and see I did something wrong, I will be more than happy to re-run my benchmarks and write a new article!)

Disassembly ?

It is not quite that easy!

I tried to get a decent disassembly from things like Matt Godbolt’s Compiler Explorer online, or the Quick Bench online utility, but the benchmarks rely on a dynamically-compiled C API function to prevent the compiler from seeing through the function call and thusly optimizing out literally everything!

So, with the online utilities I can see almost nothing:

LTO, constant-expression elision, and inlining are crazy powerful optimizations…! They get rid of nearly everything, since it’s possible to prove I’m just working with a constant value (and a constant pointer value) that puts the same value into the argument. You can see an older version of the quick bench code live here; I didn’t update it with the newest benchmark code because it had no effect on the compiler being as smart as it is and just eliding nearly everything. Thusly, we have to stick with the version where we can compile multiple things or it becomes nearly impossible to measure just the cost of the out_ptr abstraction chosen. And that cost is important to see and measure!