As part of improving sol, benchmarks are done to measure the runtime impact of many operations. These are the latest measurements to not only compare how sol2 shapes up in many areas compared to others, but areas that sol v2 (sol v3, soon™!) needs to improve on.

Preliminaries

Before I get into the numbers, I will first describe how I do the benchmarking. This is important to maintain transparency and consistency in the process, and ensure that each library is properly tested.

If I have done something incorrectly, please do inform me: these benchmarks are supposed to be fair and represent the way someone would use the library to its maximum potential, even if that way is entirely unintuitive to a beginner.

Setup

All the code and results is available at the lua-bindings-shootout repository. It is a new iteration of an old codebase that used to be called lua-bench. That one has since been deleted since it is no longer useful, and this one has superseded it.

I use Google Benchmark to benchmark the code, with a hand-rolled graph-generation tool. The tool takes many parameters, including categories and potential scaling factors, to properly draw and render graphs.

The code is compiled on Visual Studio 2017, with the latest patches, and ran on an Intel® Core i7™ 2.8 Giga-hertz desktop machine. I hesitate to try non-Visual Studio, because many libraries are incredibly finicky with their cross-platform support and do not do cross-platform CI and testing like sol and kaguya and a few others do. Plus, many are old and I had to submit pull requests (some accepted, some left open) to make sure everything worked.

I use the most up-to-date version of the code that is available, or the most popular mutation of it. For example, Luabind is no longer available as-is from Rasterbar, but the de-boostified version is and it receives general maintenance every now and then.

All libraries are built and run with Lua 5.3.4 with compatibility API defines on. I also patch any library that does not build with Lua 5.3.4 so that it builds and runs smoothly.

Lua 5.3.4 is built as a DLL. This is to provide a constant-time, hard compiler fence that cannot be optimized through: this means that what is being measured is exactly what the library’s abstractions and techniques cost, and every library plays with the same penalty.

Any benchmark that has to run Lua code will use a few techniques to ensure fairness between benchmarks:

- If possible, it will always call a function or perform an action through the same name as its counterparts (function calls will be measured through a variable named

f, variables on an object will be measured throughb, and so on). - No setup work is performed in the loop, if the library / abstraction allows for it or the code written to do so.

- If possible, the raw Lua State will be retrieved and the code will be pre-loaded, as part of the setup measurement. This code will not be timed: only running the preloaded Lua “chunk” (the preloaded code). If a framework does not support this (Selene), they are left take the penalty.

- The code is made so that desired Lua snippets run multiple times in a loop. The current number for that is 50, but if you grab the code and run the CMake Configuration process, you can choose something other than 50. That being said, it takes over 5 hours to benchmark all libraries with

--benchmark_repetitions=150and a definition of#define LUA_BINDINGS_SHOOTOUT_LUA_REPETITIONS 50passed by the command line through CMake. Please be aware of time to completion (or just have a beefier computer than I do).

I have contacted all library authors with various questions at one point or another concerning the best way to use their library. I generally keep up to date with the various ways to deal with the libraries and have perused their documentation (or lack thereof) to the fullest extent. Where documentation was lacking or did not exist, I consulted their tests (if they had any).

The syntax for tests which preload Lua code and run it expect that same syntax to work across libraries. I do not impose a syntax requirement for the C++ side, only the Lua side (companies may be migrating existing code bases, therefore it is not practical to ask them to perform sweeping Lua refactoring because a library does not support e.g. variable access with obj.member_variable and for them to use self-function obj:member_variable(value) syntax on their objects).

Note: sol3 and sol2 are identical in these benchmarks. There may be small system artefacts that prevent them from looking completely identical, but they are mostly within the boundaries of one another and within the standard deviation.

The Benchmarks

Here are the benchmark, with various notes about the requirements and findings. Note here that I always sort the benchmark with the best score first, meaning the clustering at the top of the graph is Performance Ruler.

The colors and patterns remain the same for each library name. Hopefully, this makes it easier to see which libraries have clear performance benefits. There are also standard deviation error bars on the graphs, as well as light scatter plots showing the actual distribution of values.

Table Abstractions

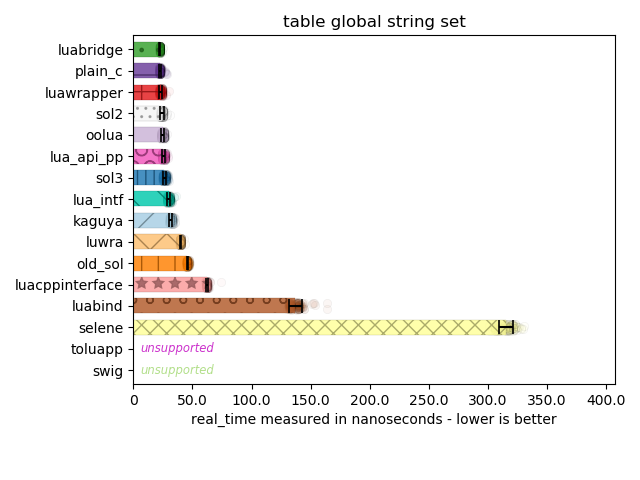

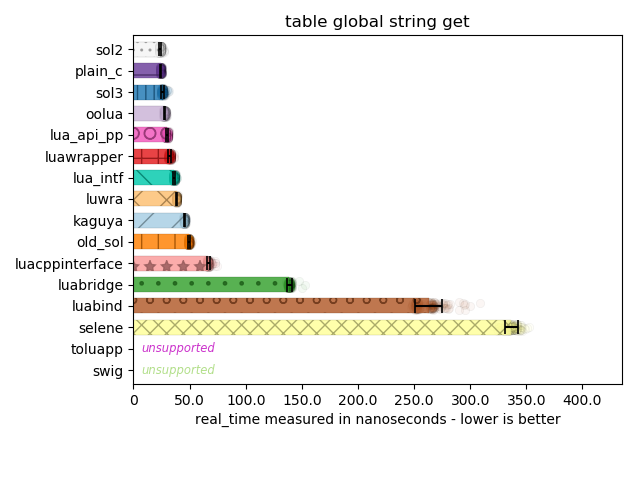

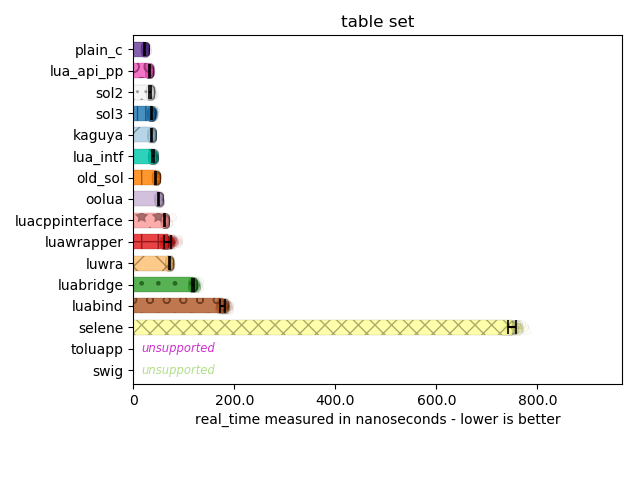

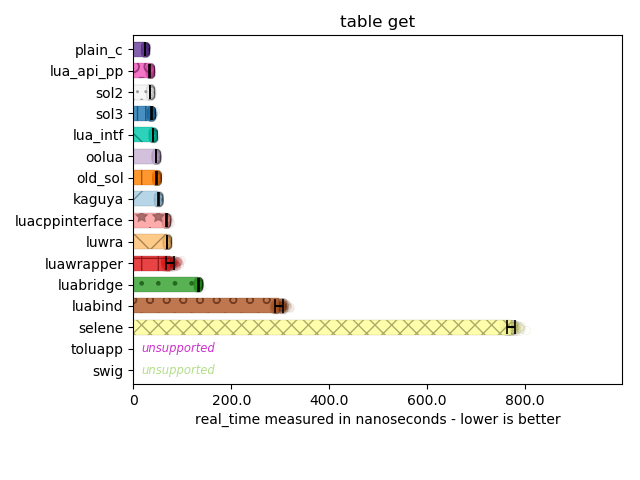

The following benchmarks measure how one interacts with a Lua table in C++. I accept various APIs for doing this since it is done in C++, from default-constructed reference-out parameters, to something closer to the int v = table["a"]["b"]["c"];.

Here, I can see most implementations perform the right optimization. Lua’s C API has multiple ways of accessing tables: there are functions for the global table with a string key, functions for a string key with a regular table, and even specializations for accessing a table with an integer key. There are also “raw” access and non-raw access versions of this as well. There are a few libraries that don’t make the distinction and suffer varying degrees of performance penalty for using the wrong API for the job.

A few libraries here also make a curious choice: rather than making you pass separate null-terminated strings to dive into nested tables, it instead writes a tiny little parser to handle every "." that appears in the strings you provide. This means you can access nested tables with "a.b.c". To use lua_getfield with such an infrastructure, an implementation would have to in-place edit the strings you pass to null-terminate them. Or, you would have to use the slower version of pushing a counted string onto the stack, then using lua_gettable to the lookup for the next “chunk”, and then continue processing the string. In either case, it’s not ideal and it does incur a performance hit, so while super convenient to specify a path in a single string, it is not advisable.

Function Calling

Here are some benchmarks for function calls. I have various different kinds of function calls I can perform in the context of Lua. I will explain each one per-graph.

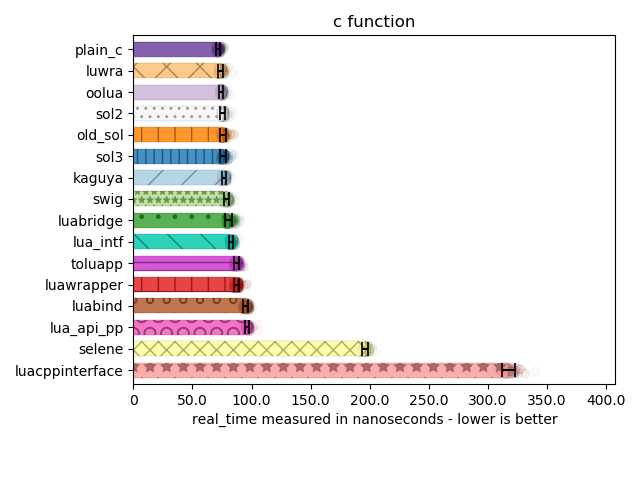

This is a very simple benchmark where I call a C++ function through some Lua code. Performance is steady across implementations, save for Luacppinterface. Much of this has to do with how efficiently arguments are pushed onto and pulled off of the stack: too much boilerplate in these mechanisms results in unwanted overhead.

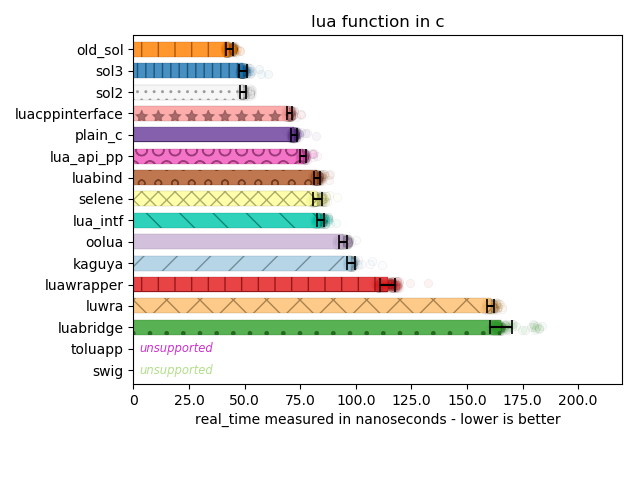

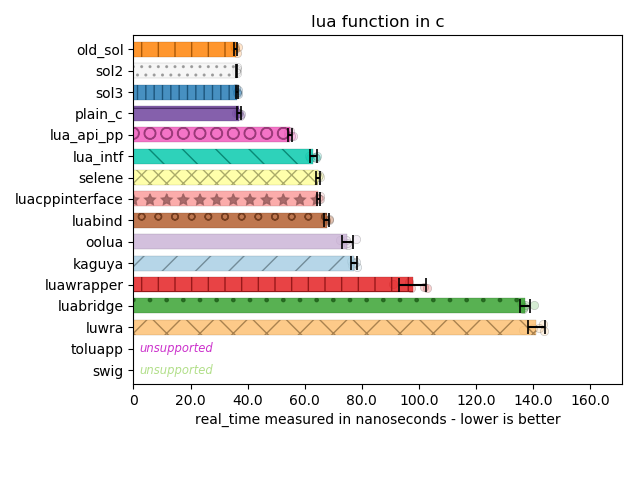

This benchmarks the function abstraction of the library, to see how efficiently it wraps up and calls lua_pcall (or lua_call). This is typically done through some abstraction lib::lua_function f = Lua["f"]; f(123);. What is most surprising here is how sol seems to outperform the handwritten C code here.

I unrolled the code for sol and compared it to the sequence of calls for plain C. One difference is that sol – when retrieving the return value of the function – boils down to double v = lua_tonumberx(L, index, &is_num); versus the typical double v = lua_tonunmber(L, index);. The latter is a macro for lua_tonumberx(L, index, NULL);.

The other difference is in library’s and handwritten’s code use in lua_call (which defers to lua_callk) versus lua_pcall (which defers to lua_pcallk). lua_call does not attempt to set any error handlers or perform any safety. You would think that lua_call would have equal (or mostly negligible) performance to lua_pcall if you set all the continuation and error-checking arguments to be their null types.

Here is a (quick, 5-sample, multiple-iterations) benchmark of the same thing using lua_call rather than lua_pcall:

Bam, now its all even!

This just goes to show you that even a null check or some defaulting can cost your API in terms of speed. There is a reason why both functions are provided in the API: if you know your code is not going to fail, prefer the fast version (sol does this by giving both sol::protected_function and sol::unsafe_function in v2.x.x and onward; sol::function picks the safe or unsafe version based on the SOL_SAFE_FUNCTIONS configuration macro).

There are many other benchmarks for functions. You can see them all at the main repository, or on the sol3 benchmarks page. Be aware that these numbers may look different, as it pulls from the latest, whereas these graphs have been tied to a specific commit at the time of post.

Class Types - Functions and Variables

Classes are an interesting beast. I primarily test the interop inside of Lua and the features of those classes within Lua. Since these tests deal with Lua syntax, they are much more strict in what is considered “support” of the features (but the C++ code has no requirements on what it looks like in order to support the syntax and be fast). The binding code can take any form, so long as it supports the given Lua syntax described below.

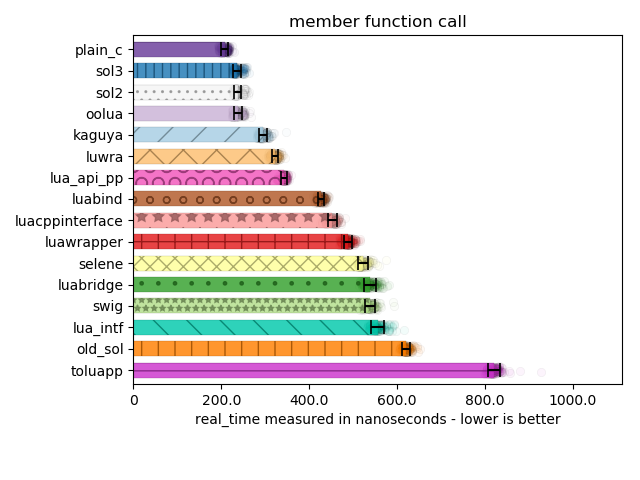

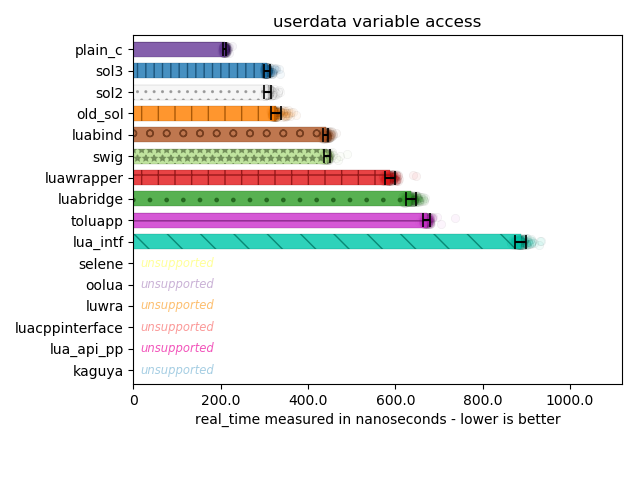

Below are tests for member function calls (in Lua with obj:mem_func(), and member variable access (in Lua with obj.my_var = 20 and similar getter) on customized usertypes / userdata:

The support story drops off sharply here between member functions and member variables. Many library writers did not want to invest the time to learn how to make both member function and member variable lookup worked (it is a non-trivial exploration for C binding code) and – even if some did – some did not want to take the fixed overhead penalty for having to retrieve both member variables and member functions from C++. In particular, kaguya, selene, and a few other libraries lost support because they immediately reached for automatic creation of obj:member_variable_get/set() or overloaded obj:member_variable()/obj:member_variable(value) functions.

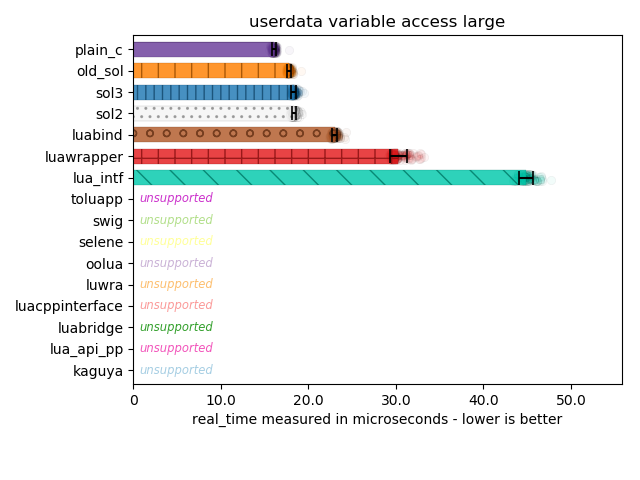

Here I measure the pathological case of where I bind over 50 member variables of similar names, and with different types (mostly double, int, and int64_t). This is more or less a stress test to tease out performance differences between lookup strategies.

Some libraries drop off in support here not because they do not support more than 50 member variables, but because they forgot to write code to handle int64_t, and thusly butchers its return value or cannot set it equal to a number from Lua.

While it is arguable whether or not supporting int64_t makes sense pre-Lua 5.3 (where integers were not explicitly supported and a user only had 53 bits of integral precision because everything was a double), the fact that many libraries do not bother to address it is rather concerning.

It is worth mentioning the Plain C code here isn’t entirely a full C solution. Purely out of laziness, I made an unordered_map of const char* to std::unique_ptr thunks that retrieve memory and pull it out. The plain C(++) solution here is dominating in performance, but that is mostly due to the lookup map using const char* as its lookup mechanism. Other solutions have to create temporary strings, and so suffer allocation penalties (somewhat avoided in this benchmark: the variable names are var1 to var50, so Small String Optimization prevents too big of a hit. It still does not beat plain old C-strings for hashing and lookup speed, however).

Class Types - Inheritance

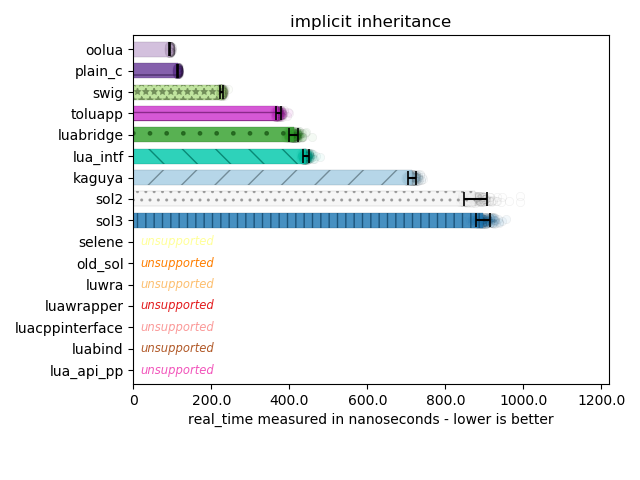

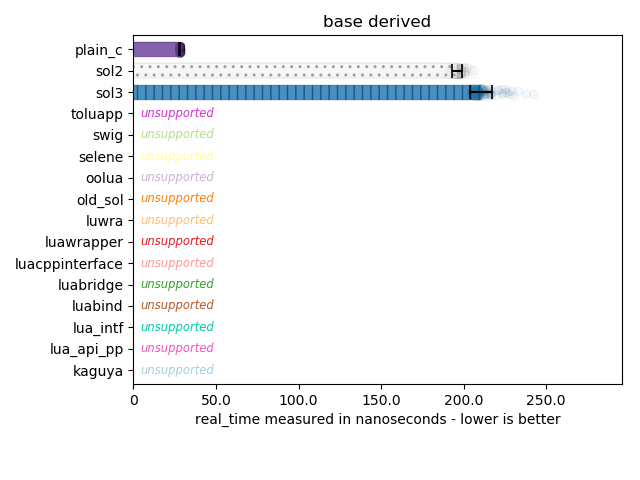

Inheritance is an incredibly rough beast. There are only 2 benchmarks I do related to this, and both are not pretty for sol:

This benchmark is a little bit more lenient. The actual Lua code here only calls one of 2 inherited functions: if you write your bindings correctly with Lua-Intf and Luabridge, you can get away with the fact that Lua-Intf and Luabridge don’t actually support multiple inheritance. In the future I will probably make the benchmark check both depended-on functions, in which case a few more frameworks will drop into “unsupported” land. But, as you can see, Macro-based solutions like OOLua beat out the typical hand-written inheritance situation in Plain C and most other libraries. SWIG also performs well because it forwards all base member function and variable registration onto its derived classes, saving itself from having to perform a chained lookup.

Chained lookup is exactly what plagues sol in this case: there is a complicated series of indirections and lookups to check for base classes and walk each one. Not to mention that base class lookup is entirely linear: due to the way the code is registered, sol checks the proper base class with the right entry last, resulting in an unfortunate speed drop. This is something I plan to fix for sol3 and have been warning about in the documentation for a long time.

This shows part of the reason why sol is slow in the implicit inheritance benchmark. sol allows the user to obtain the base class of a derived member at will in raw C++ code. Almost no other library has that kind of support story. Plain C is fast because I cheat heavily: I simply get the proper derived type and then static_cast to the right base type. In a real system, you often do not have that kind of fore-knowledge. Still, it serves as a good comparison to what the theoretical fastest would be.

Optional / Safety

Another big concern is how deeply can you dive into a nested table and properly detect that a given query/lookup into the Lua virtual machine will fail. Making choices based on that information allows the user to avoid segfaulting the system when it performs a “too deep” lookup for Lua. For example, even if a does not exist as an element on a table, it is not an error because it would just return nil. But a.b would crash is a did not exist in the table, leaving the code to try and access nil for b and thus invoke the Lua VM’s panic function.

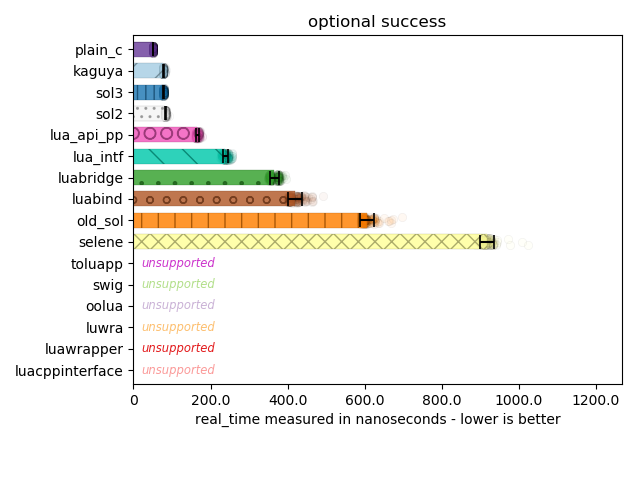

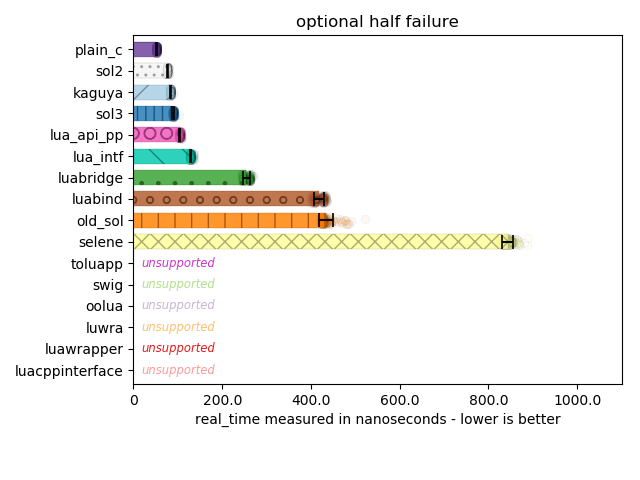

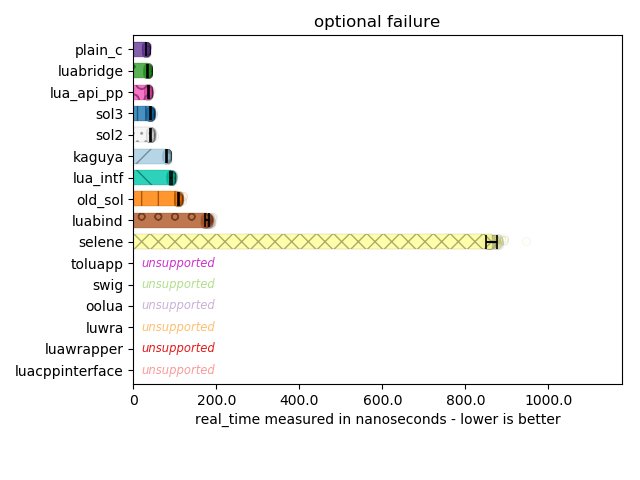

Below are libraries that (successfully) allow you to avoid the segfault and check if something exists in a nested tables resulting from executing the pre-script "warble = { value = 3 }". For the “half failure” test, I remove the value: for the full “failure” test, there is no table at all.

Important to note that asides from Selene’s performance here, most libraries are good at performing the minimum necessary work to check and avoid failure, or to give success. The fastest code simply performs type checks all the way down. sol here loses some performance because I check if a type is more than just a table or not: e.g., a userdata can simulate table-like properties by overriding metamethods, and so there is a slight bit of overhead here for the goal of having a more robust table abstraction in C++. It is important for many code bases to handle “callable-alike” and “table-alike” types, and it is incredibly frustrating when code ultimately fails due to a cruddy assertion like assert(lua_istable(L, index));.

Benchmark Implementation Notes

The Plain C implementation does some things which are not intuitive or common amongst most code bases using the Lua C API.

For code which calls a Lua function from C++, it becomes clear that storing values and persisting a reference count in C++ for an object representation of the Lua type is a huge win (Lua function, multi return, and other benchmarks that call a Lua function through C++).

It is slightly unintuitive in the Plain C API to store something in the registry first, because just calling lua_getglobal(L, "my_func") puts my_func on the stack exactly where I need it to be before setting up said stack to perform a lua_pcall. Older benchmarks demonstrate a clear win when doing this too, but I have eliminated that difference for the sake of making sure the most performant way of doing things is benchmarked.

Observations

Macros, reflection engines such as SWIG, and other DSL-based solutions which pre-ordain base class relationships have clear wins for inheritance usage. The way they do this is by aggregating all the methods from the base classes into the super class’s lookup table, completely avoiding any runtime chaining scheme. sol clearly loses out here.

Unfortunately, many of these libraries do not expose ways to deal with inheritance in the C++ side by regular user code: it gets baked into Lua, but interacting with tables C++ side becomes a pain. This is where sol’s flexibility shines despite its inheritance issues.

Many libraries have not fully thought through their table abstractions. This makes sol’s abstractions fairly advanced compared to the others, but still capable of the same level of performance.

There are some techniques (storing a reference count in C++) which have clear wins over others.

My favorite library here – besides sol, which I’m the author of and heavily biased towards – is kaguya. If I did not develop sol, I would be using kaguya, especially since it offers C++03 support using Boost.

“Hey, Can You Benchmark –”

Yes, I will be happy to benchmark whatever library/framework/etc. that you come across, provided it has some form of documentation explaining how to use it. Whether that is actual documentation, tests, or examples, I need some amount of explanation and help to do what I am going to do.

If you have a library you want me to benchmark, please make sure it has some amount of documentation. Some of the libraries used here have no documentation, are defunct, or are changed and they did not update the documentation: these libraries were hell to debug errors and fix performance issues. I am happy to benchmark and check, except in the case where I have to start guessing. Please do not make me begin to guess how to properly use a library.

This was a fairly deep dive, but that’s it for now. There are some interesting things from these benchmarks that will likely result in new blog posts! Until then,

see you later. ♥

P.S.:

Some future directions for this could include checking memory usage for each runtime as well. There’s a whole host of measurements beyond just performance that would be quite important!